For many patients, radiation therapy is an essential part of breast cancer treatment. Yet months or even years after finishing radiation, up to 16% of patients can develop late side effects that can negatively affect their quality of life.1-5

Currently, clinicians do not have a way to predict who might be at risk for these delayed reactions. New genetic research from MiraKind, some of which has already helped doctors identify prostate cancer patients at higher risk of side effects, is changing that.

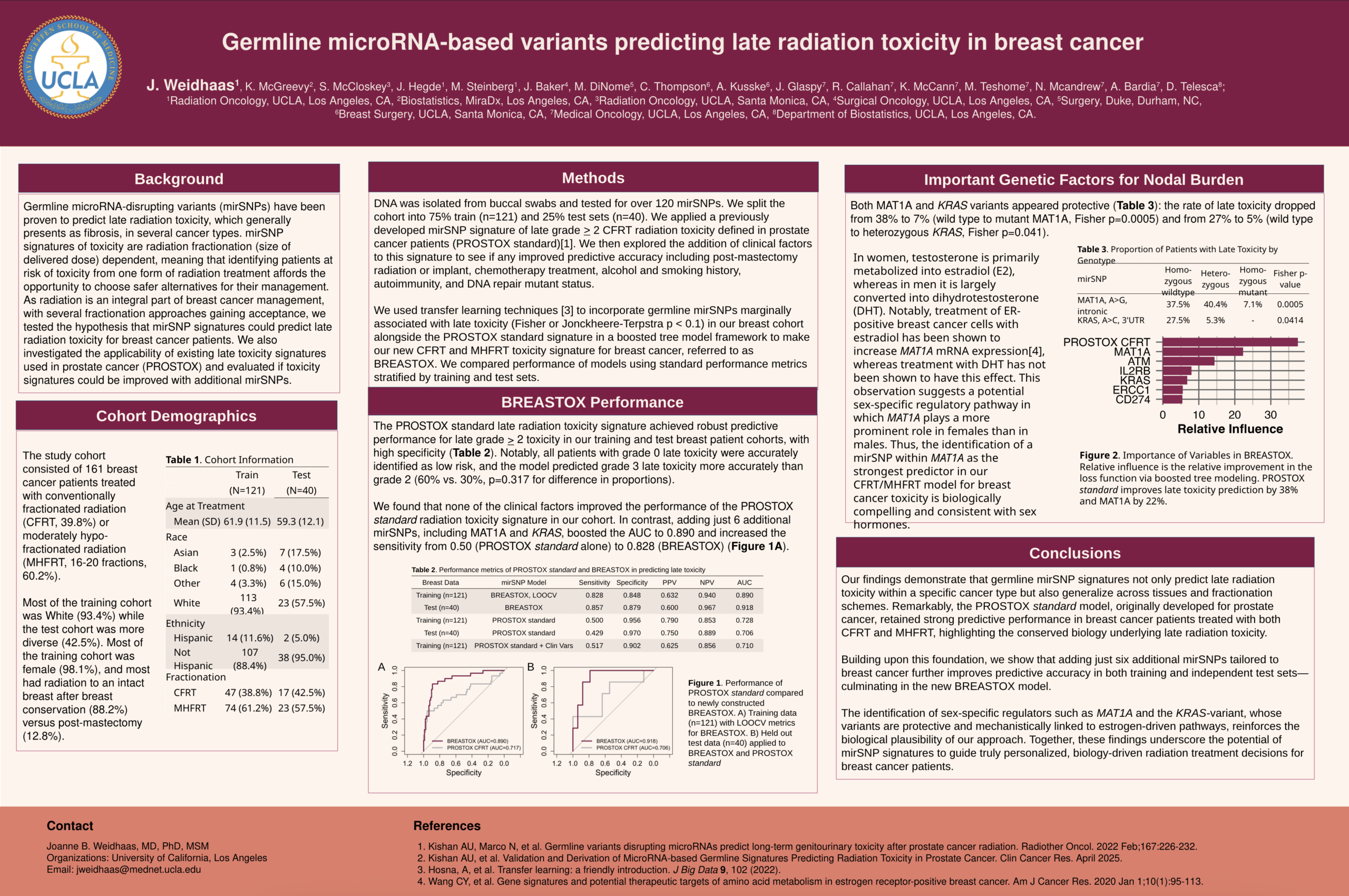

The study led by Dr. Joanne Weidhaas, founder of MiraKind, along with fellow researchers at UCLA, asked an important question: Could inherited genetic differences help identify breast cancer patients at higher risk for late radiation toxicity before treatment?

Before we answer this question, it helps to first look at how radiation can cause late side effects, what these are in breast cancer, and how a person’s genetics can influence their risk.

What are late radiation side effects in breast cancer?

Localized breast cancer refers to cancer that is confined to the breast or nearby lymph nodes and has not spread to other parts of the body. Finding it early is important because treatment is often very successful, and many people go on to lead long lives afterward.

Treatment involves surgery to remove the tumor and usually some local lymph nodes. Sometimes only the tumor is removed, which is called a lumpectomy, and other times the entire breast is removed, known as a mastectomy. After surgery, doctors often recommend radiation therapy to lower the chance of the cancer returning.6

Radiation works by targeting any remaining cancer cells that might be left behind so they can’t grow back. But radiation can also affect nearby healthy tissue, and when these effects are negative, this is known as radiation toxicity.

Radiation toxicity can occur during or after treatment. When toxicity occurs during or soon after treatment, it is referred to as an “acute” side effect. When radiation toxicity develops gradually over months or even years, it is referred to as a “late” side effect. While both types of side effects matter to doctors and patients, late side effects can be permanent and may interfere with day-to-day activities.

How radiation can lead to fibrosis

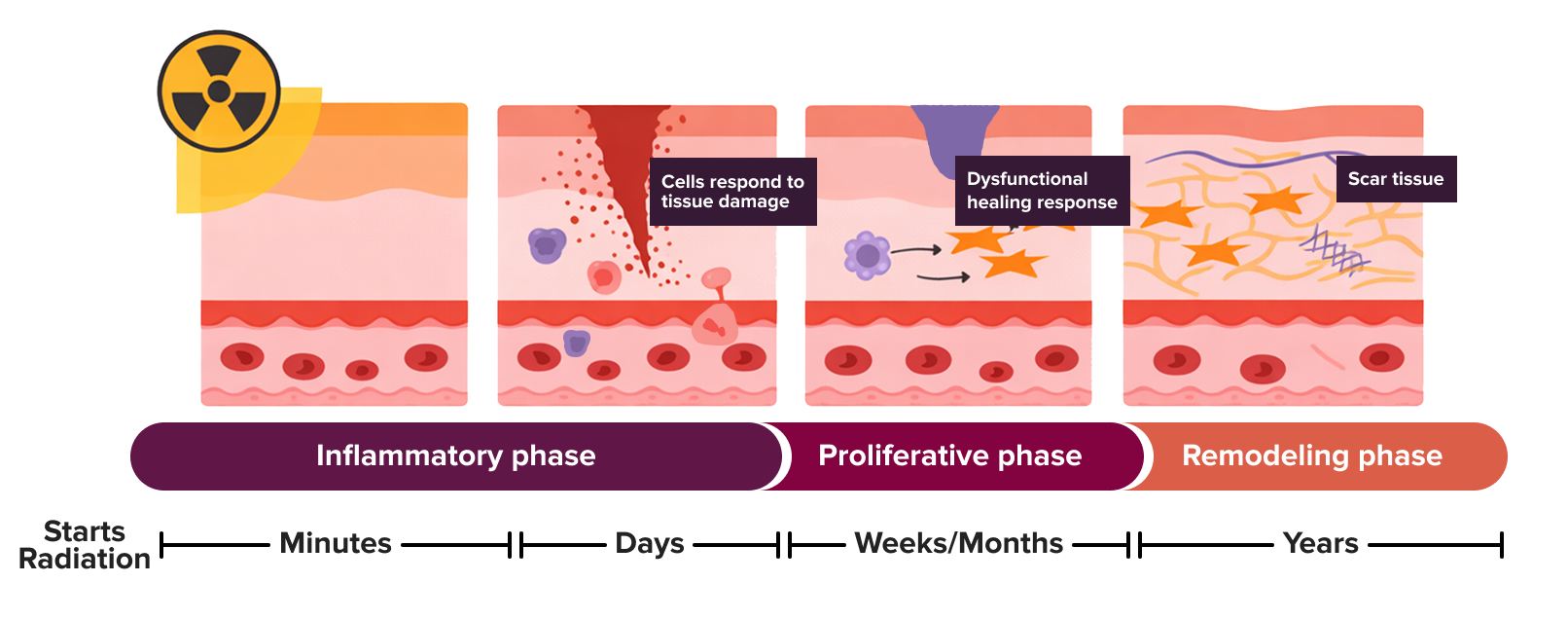

In breast cancer treated with radiation therapy, late toxicity often presents as fibrosis, one of the most common late radiation side effects. It is thought to occur when radiation triggers ongoing inflammation and interferes with the normal healing process.7 Over time, healthy tissue is replaced with dense, scar-like tissue.8-11

A Closer Look at Radiation-Induced Fibrosis

Radiation can trigger inflammation as part of the body’s natural healing response. As the tissue repairs itself, scar-like tissue may form. If this process continues for too long, the tissue can gradually become thicker or firmer, referred to as fibrosis. Figure adapted from Maria Jimenez-Socha et al., “Radiation-Induced Fibrosis in Head and Neck Cancer: Challenges and Future Therapeutic Strategies for Vocal Fold Treatments,” Cancers, 2025, DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17071108. CC-BY 4.0 license.

Fibrosis can make the breast feel thicker or tighter and change its shape, or it can cause tightness and discomfort in the chest wall. This can be especially problematic for patients who have had breast reconstruction after surgery. In severe cases, besides deformity of the breast, fibrosis can cause pain, stiffness, or limited movement in the arm and shoulder. These changes can mean the difference between living not just a long life, but a comfortable one where pre-treatment activities can be fully enjoyed.

How genetics can influence radiation response

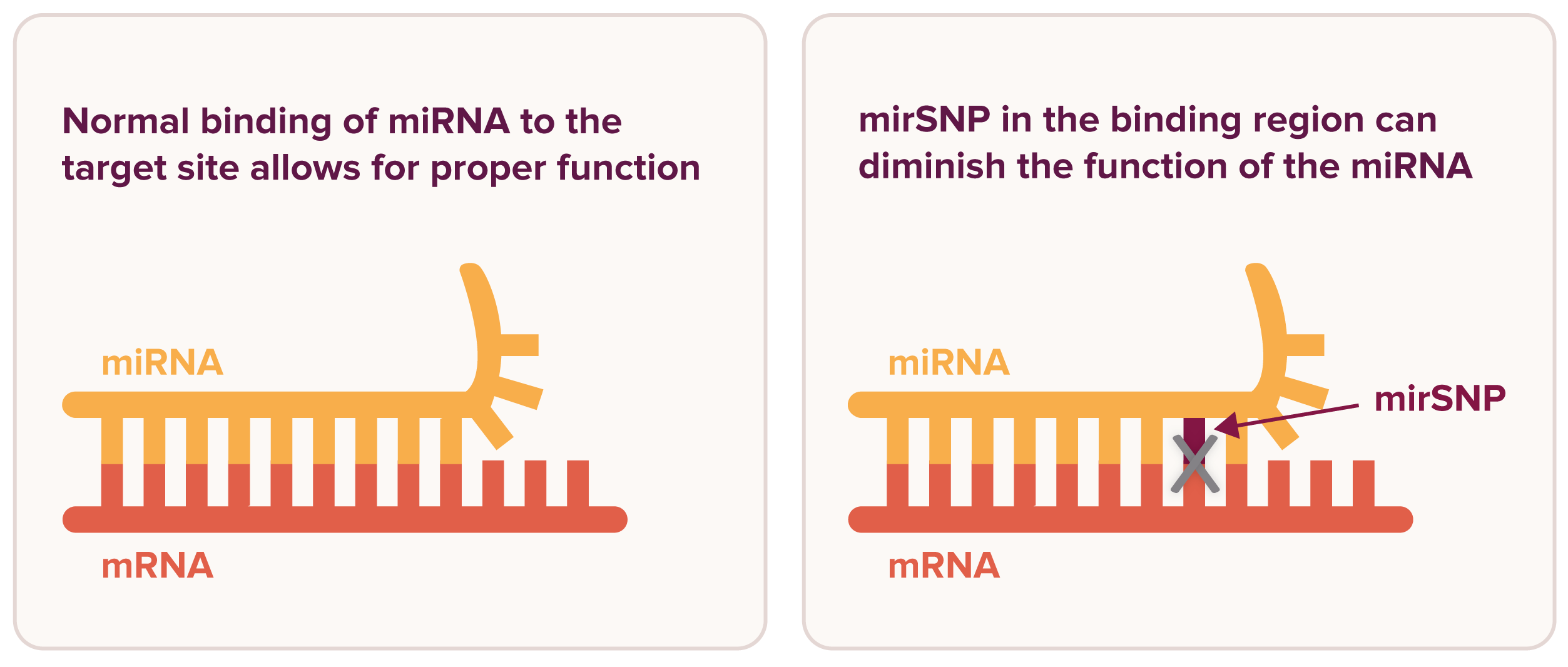

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small molecules that help cells manage stress and cellular damage, including the damage caused by radiation. Some people are born with variations in their miRNAs or in the sites where they bind. These inherited variants are known as microRNA single nucleotide polymorphisms, or more simply, mirSNPs, and they can influence how miRNAs function both at a baseline level and in response to stress.

Proper vs. Reduced miRNA Binding

miRNAs influence gene expression by binding to messenger RNA (mRNA). A mirSNP in the miRNA binding site on the mRNA or in the miRNA itself can influence the body’s response to stress and cellular damage. Figure adapted from Malhotra et al., “Breast Cancer and miR‑SNPs: The Importance of miR Germ-Line Genetics,” Non-Coding RNA, 2019, DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/ncrna5010027. CC-BY 4.0 license.

How mirSNPs predict late toxicity in prostate cancer

Some mirSNPs have been linked to cancer risk and differences in treatment response, including radiation-induced late side effects.12-15 In earlier research, Dr. Weidhaas and colleagues identified specific combinations of mirSNPs, known as mirSNP signatures, that predict which patients with prostate cancer were at higher risk of developing late toxicity after radiation therapy.14,16-19

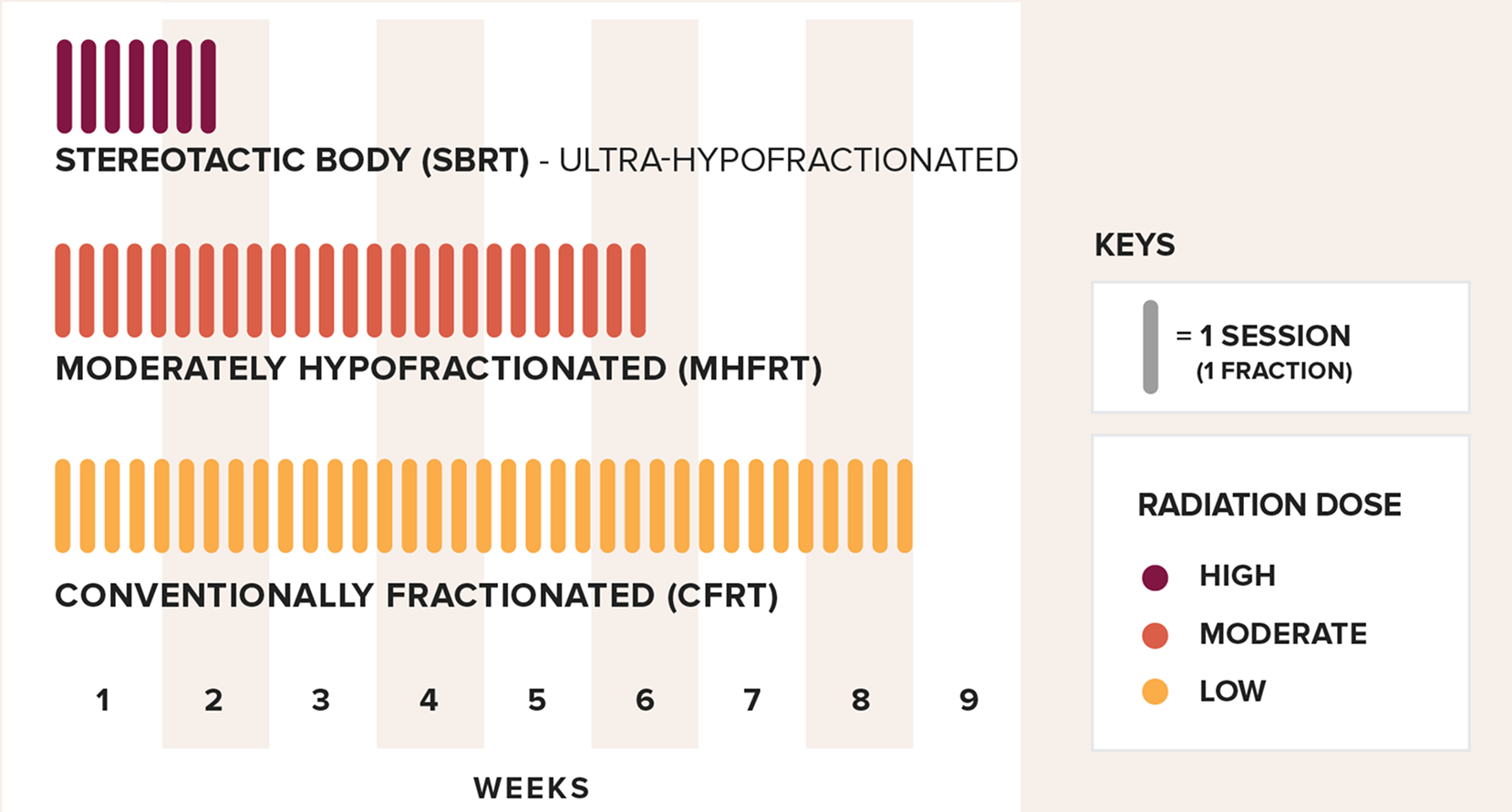

The research identified two distinct mirSNP signatures, each associated with a specific radiation treatment approach. One signature predicted late toxicity from stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT), while the other predicted the same toxicity from conventionally or moderately fractionated (CFRT/MHFRT) radiation therapy. Because these signatures are dependent on the type of radiation treatment approach, a patient at high risk for late side effects with one treatment regimen may not be at high risk with another.

Radiation Therapy Regimens

Fractionation divides a patient’s total radiation dose into smaller, usually daily doses (sessions) over a set time frame. SBRT delivers the full dose over a few days, with a high dose given in each session. In contrast, MHFRT and CFRT deliver the total dose over several weeks, using moderate or low doses per session.

This work ultimately led to the development of genetic tests now used in prostate cancer care to identify patients at increased risk of late side effects. PROSTOX™ Ultra identifies patients at higher risk following SBRT, while PROSTOX Standard identifies patients at higher risk following CFRT and MHFRT.

Because mirSNPs are inherited and treatment type-dependent, the researchers considered whether these variants could identify patients at higher risk of late toxicity in other cancers treated with the same radiation approach.

This brings us back to the question posed at the start of this article: Could inherited genetic differences help identify early-stage breast cancer patients at higher risk for late toxicity before treatment?

Testing genetic risk for late toxicity in breast cancer

To answer this question, Dr. Weidhaas and colleagues at UCLA tested whether the mirSNP signature from the PROSTOX Standard test could predict late toxicity in breast cancer patients being treated with MHFRT or CFRT. The study included 121 patients, all of whom had received radiation therapy.

Here’s what they did:

- Patients were treated with radiation therapy (CFRT or MHFRT) for breast cancer.

- Their DNA was analyzed using the PROSTOX Standard test and additional mirSNPs.

- Patients were monitored for two years or more after treatment to track side effects.

Here’s what they found:

- The PROSTOX Standard test successfully identified patients who were more likely to develop late radiation toxicity.

- The addition of five additional mirSNPs to the test strengthened its ability to detect breast cancer patients at high risk of late radiation toxicity.

- Clinical factors (non-genetic factors), like other treatments or health history, did not explain who was more likely to develop late radiation toxicity.

Late radiation side effects are influenced by genetics

These findings further confirm that late side effects from radiation are not random. Instead, inherited genetics play an important role in how healthy tissue responds to treatment. As a result, a mirSNP signature developed for one cancer can also help identify higher-risk patients in another cancer when the same radiation approach is used.

Access the preliminary findings:

The poster, “Germline microRNA-based variants predicting late radiation toxicity in breast cancer,” was presented at the December 2025 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

Future tests and research

This research represents an important advancement in breast cancer care and has led to the development of a genetic test to predict late radiation side effects after CFRT or MHFRT. The test will soon be available for doctors and breast cancer patients.

Although CFRT and MHFRT have been the primary focus of this study and are the most common methods for treating breast cancer, they are not the only radiation approaches. Shorter treatment courses, such as SBRT, are also beginning to be used. Ongoing research is examining the signatures of late radiation toxicity using this approach as well.

Implications for patients and the future of breast cancer care

Work by Dr. Weidhaas and colleagues is helping to identify which breast cancer patients may be at risk of late radiation toxicity. A test based on a patient’s unique genetics could one day guide safer, more personalized treatment decisions, allowing doctors and patients to choose approaches that avoid side effects like fibrosis while still effectively treating the cancer.

While currently there are no known ways to prevent radiation fibrosis, staying on top of follow-up care and paying attention to changes in your body are the best ways to manage symptoms. If you notice any changes in your breast, skin, or shoulder mobility, let your doctors know right away. Early treatment can help reduce symptoms and make them easier to manage over time.

References

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33226140/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16335014/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31851743/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33898697/

- https://www.redjournal.org/article/S0360-3016(22)03523-4/fulltext

- https://www.thelancet.com/pdfs/journals/lancet/PIIS0140-6736(14)60488-8.pdf

- https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/imm.13788

- https://www.thelancet.com/pdfs/journals/lanonc/PIIS1470-2045(13)70386-3.pdf

- https://www.redjournal.org/article/S0360-3016(17)31700-5/pdf

- https://www.redjournal.org/article/S0360-3016(02)04120-2/abstract

- https://www.ejcancer.com/article/S0959-8049(97)00312-2/abstract

- https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamaoncology/fullarticle/2594275

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10566451/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8979583/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7189949/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6484596/

- https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.2020.38.6_suppl.163

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2405630823000198

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40192540/

Leave a Reply