When we talk about breast cancer, pregnancy is rarely part of the conversation. We tend to think of breast cancer as a disease of older age, not something that happens to young women at the start of raising a family. Yet the reality is changing; more pregnant and postpartum women are being diagnosed than many people realize.

What is pregnancy-associated breast cancer (PABC)?

Did you know that about 10% of all new breast cancer cases occur in women under 45?1 This proportion has been rising by roughly 1.1% per year over the past decade.2 More than half of these cases are PABCs, which are diagnosed during pregnancy or within one to five years after childbirth.3,4

PABC remains relatively rare, with an estimated 19.2 cases per 100,000 pregnancies, or roughly 2 in 10,000.5 Despite its rarity, the rise in breast cancer among young women makes understanding PABC increasingly important, along with improving treatment options and awareness.

Before we look at the features of PABC, it helps to understand how the breasts change during a woman’s life, since these changes can influence how the disease develops.

Breasts are a dynamic organ

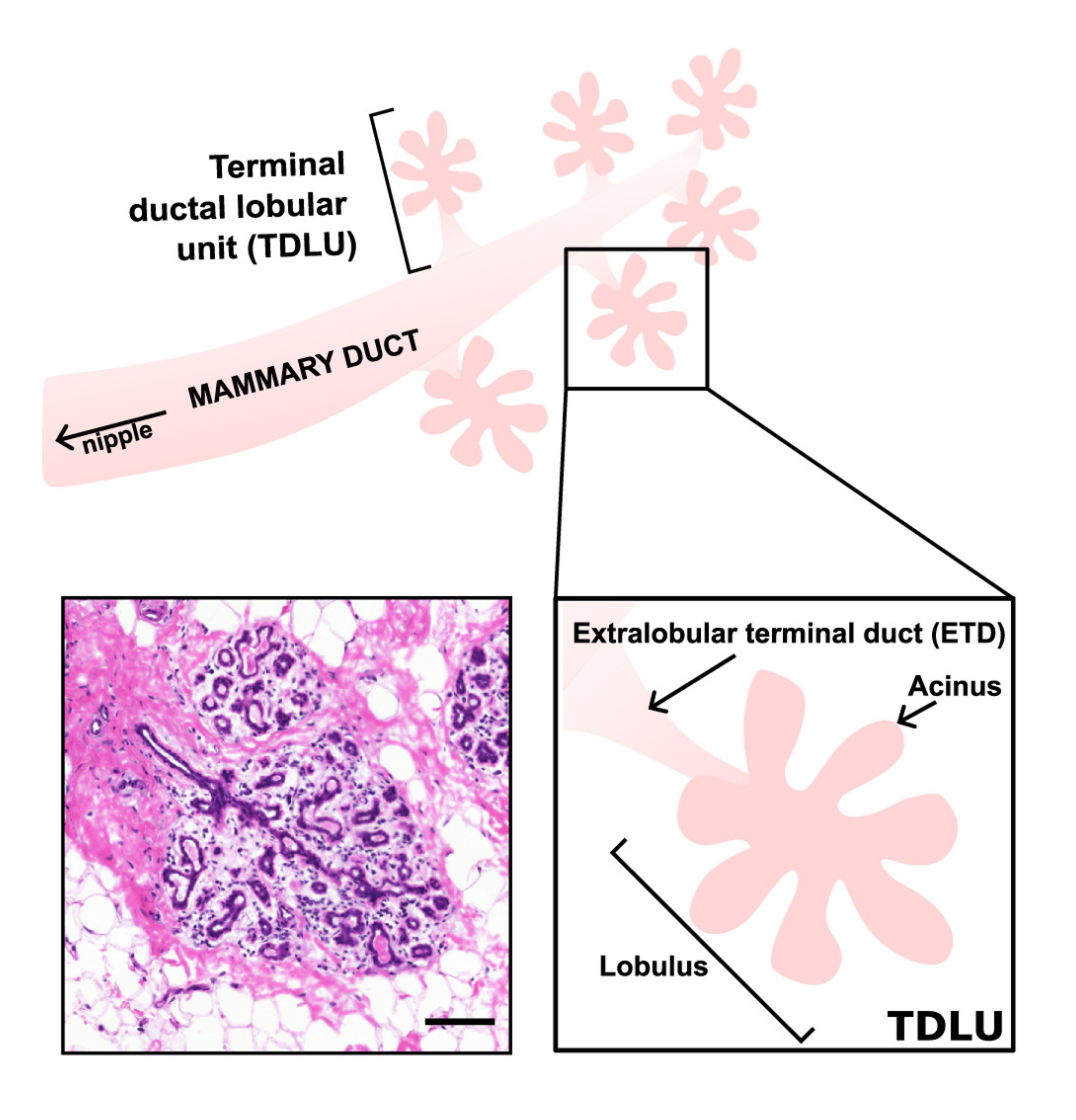

Breasts grow and change during puberty, pregnancy, the postpartum period, and menopause. The main functional unit of the breast is the terminal duct lobular unit, or TDLU. Each TDLU contains small ducts and milk-producing structures. TDLUs form and mature during puberty under the influence of estrogen.6

Structure of a TDLU

A diagram of a terminal ductal lobular unit (TDLU), the basic milk-producing unit of the breast, alongside a real breast tissue section stained to show cell and tissue patterns. Together, they show how the parts of a TDLU are arranged and how they appear in real tissue. Reprinted from Paavolainen et al., “Volumetric analysis of the terminal ductal lobular unit architecture and cell phenotypes in the human breast,” Cell Reports, 2024, DOI: 10.1016/j.celrep.2024.114837. Used under CC-BY 4.0 license.

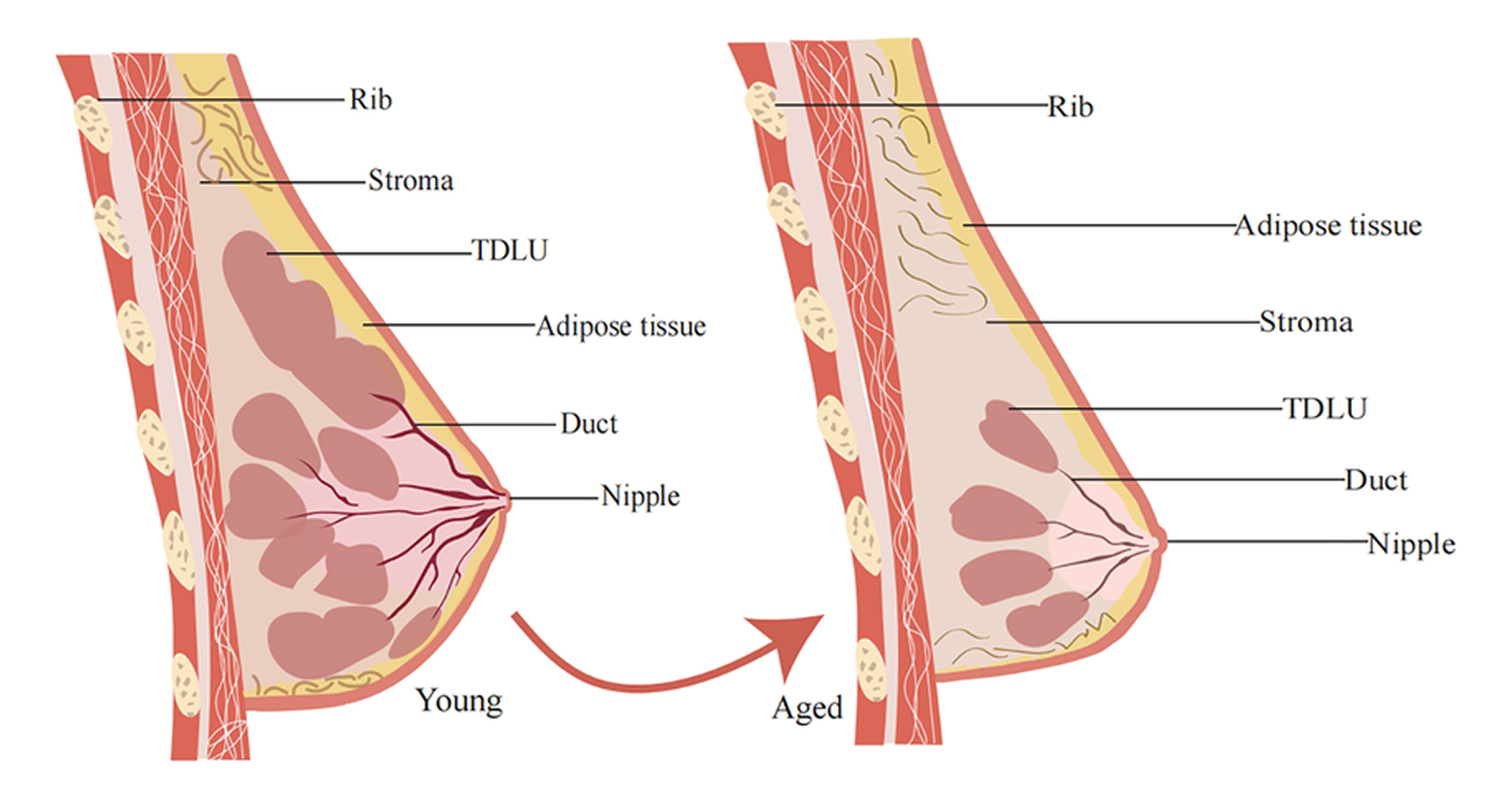

During pregnancy, rising hormone levels cause the TDLUs to expand and prepare for milk production.7,8 After breastfeeding ends, or if milk production does not start, the glands shrink and return to their pre-pregnancy state in a process called post-lactational involution.8-10

As women age, the milk-producing TDLUs also gradually shrink and are replaced by fatty tissue. This age-related involution usually begins around age 30 and continues well into the 40s.11 Around menopause, the natural drop in estrogen helps the TDLUs shrink further, gradually replacing them with fatty and supportive tissue.10,11

Mammary Gland Involution

This schematic shows the basic structure of the mammary gland. During involution, most TDLUs are gradually lost and replaced by fatty and supportive tissue. Reprinted from Li et al., “Relationship between breast tissue involution and breast cancer.” Frontiers in Oncology, 2025, DOI: 10.3389/fonc.2025.1420350. Used under CC-BY 4.0 license.

How involution shapes breast cancer risk

Since most breast cancer precursors develop in the TDLUs, the changes that occur during involution can influence cancer risk.12 Normal involution creates a short period of inflammation and tissue remodeling, and if involution is delayed or incomplete, these changes can persist longer. Both situations can create conditions that make it easier for early cancer cells to survive or grow.12,13

Several factors can influence how fully TDLUs shrink and remodel:

- Inflammation: Chronic or persistent inflammation during involution may slow the normal shrinkage and remodeling of TDLUs.14

- Reproductive history: Having children later or not breastfeeding can result in more persistent TDLUs.10

- Hormonal changes: Drops in estrogen after childbirth or during menopause contribute to involution, and variations in hormone levels may affect how fully this process occurs.8,10

- Biological variation: Genetic factors and other intrinsic traits can influence how completely TDLUs shrink.12

Together, these factors may increase cancer risk and help set the stage for the distinctive biology observed in PABC.

How PABC tumors are different

Early research showed that PABC isn’t like other breast cancers. These tumors have unique genetic profiles that affect immunity, cell growth, and cell communication.15 They are also more likely to be triple-negative or HER2-positive, receptor-defined subtypes that can be more aggressive.16-19

Because of these traits, PABC was shown in some studies to have a poorer prognosis compared to breast cancer in young women who have never given birth.20-22 Yet other studies saw no difference,23,24 creating confusion about how to best treat young mothers with breast cancer.

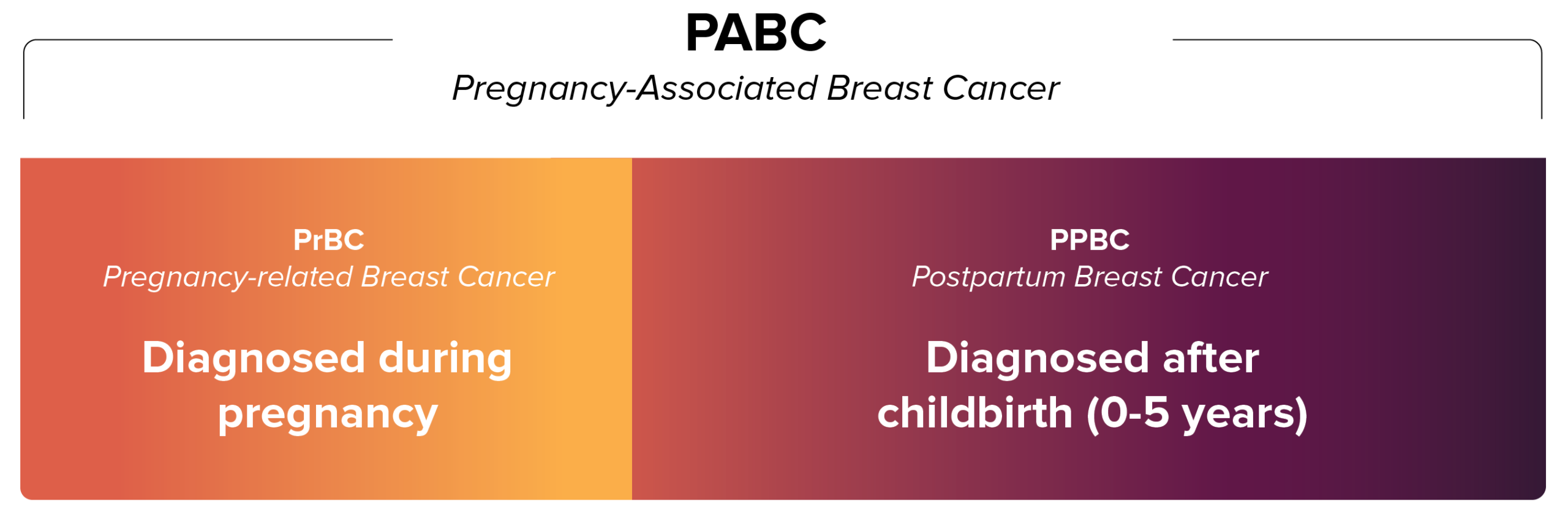

PABC: Two distinct types

As research has progressed, it has come to light that PABC isn’t just one type of breast cancer but two, due to their unique biological attributes and prognoses.25 Together, these are called PABC, but separately they are pregnancy-related breast cancer (PrBC) and postpartum breast cancer (PPBC).

The separation of PABC into two unique types has important implications. Although PrBC can show aggressive features under the microscope, survival rates are similar to those of young women with breast cancer who have never given birth.26,27 The similar survival rates show that PrBC can usually be treated much like breast cancer in young women who are not pregnant, with some adjustments depending on the stage of pregnancy.

However, PPBC can be associated with worse survival rates and has more than twice the risk of metastasis compared with breast cancer diagnosed in young women during pregnancy.25,28,29 This feature, first noted in earlier PABC studies, was a key factor in recognizing that PABC comprises two distinct types.

PPBC tumors are more often triple-negative or HER2-positive, patterns also observed in PABC overall. Interestingly, some PPBC tumors are estrogen receptor–positive (ER+), which are usually more responsive to treatment. Postpartum ER+ tumors often behave differently however, and do not respond as well compared to other ER+ tumors, emphasizing the unique biology of PPBC.30

And it turns out that PPBC is far more common than PrBC. While PrBC represents roughly 4% of breast cancer cases in women under 45, PPBC accounts for 35% to 55% in this same age group.27,28,31

Why is PABC becoming more common?

Breast cancer can occur at any age, and its risk is influenced by factors such as family history, genetics, obesity, smoking, etc.32 In addition to these individual risk factors, broader societal trends, such as the age at which women have children, could be contributing to the rise in PABC.

Childbearing age

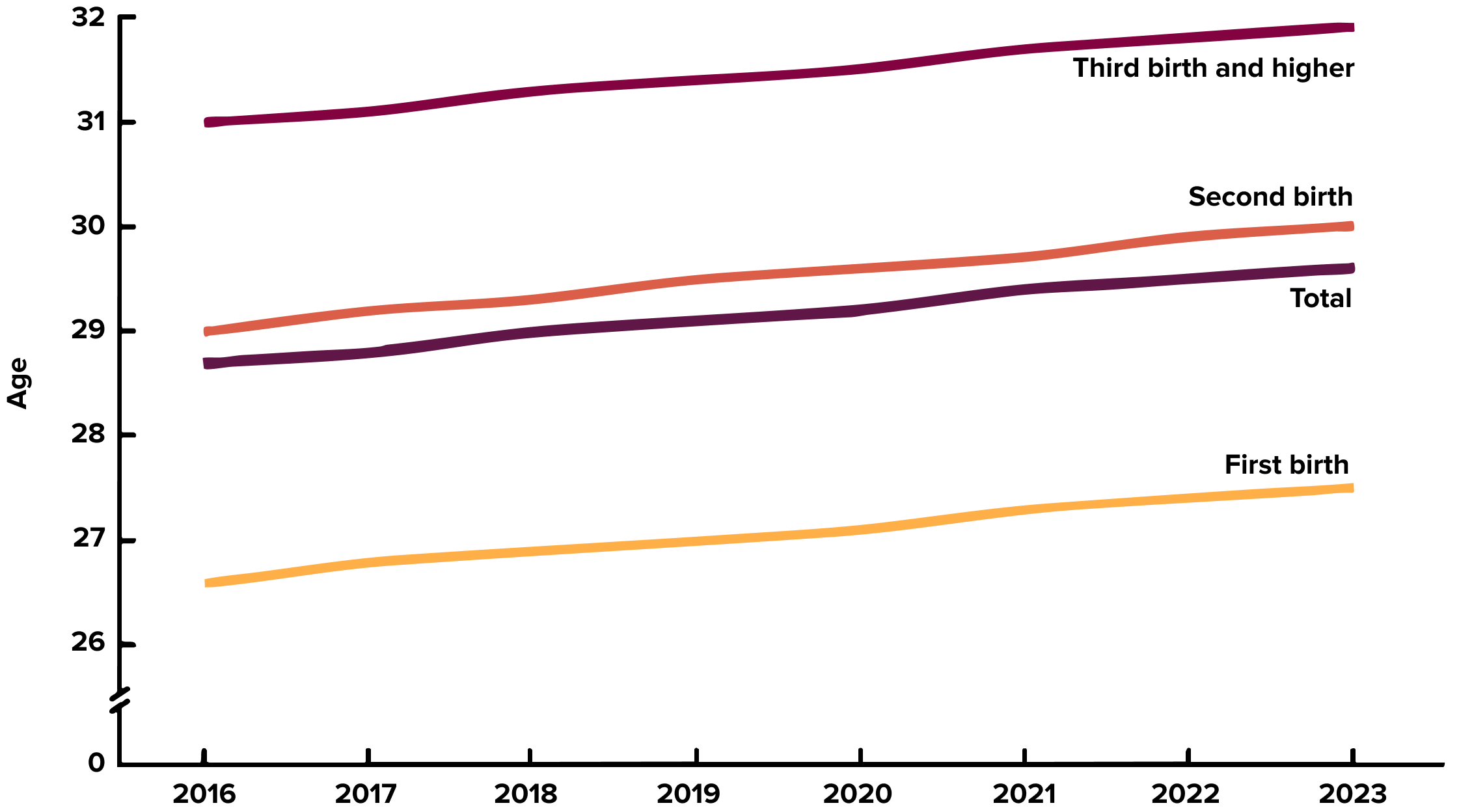

Having a child at a younger age can lower the risk of breast cancer later in life. But more women are waiting longer to start their families, which can change that risk.

In the U.S., for example, the average age of first-time mothers went from 26.6 in 2016 to 27.5 in 2023. The same is true for second, third, and later pregnancies, with more women over 30 having children now than in the past.33,34

Rising Maternal Age Across Births

Age of mothers at first, second, and later births increased from 2016 to 2023. Image courtesy of CDC.

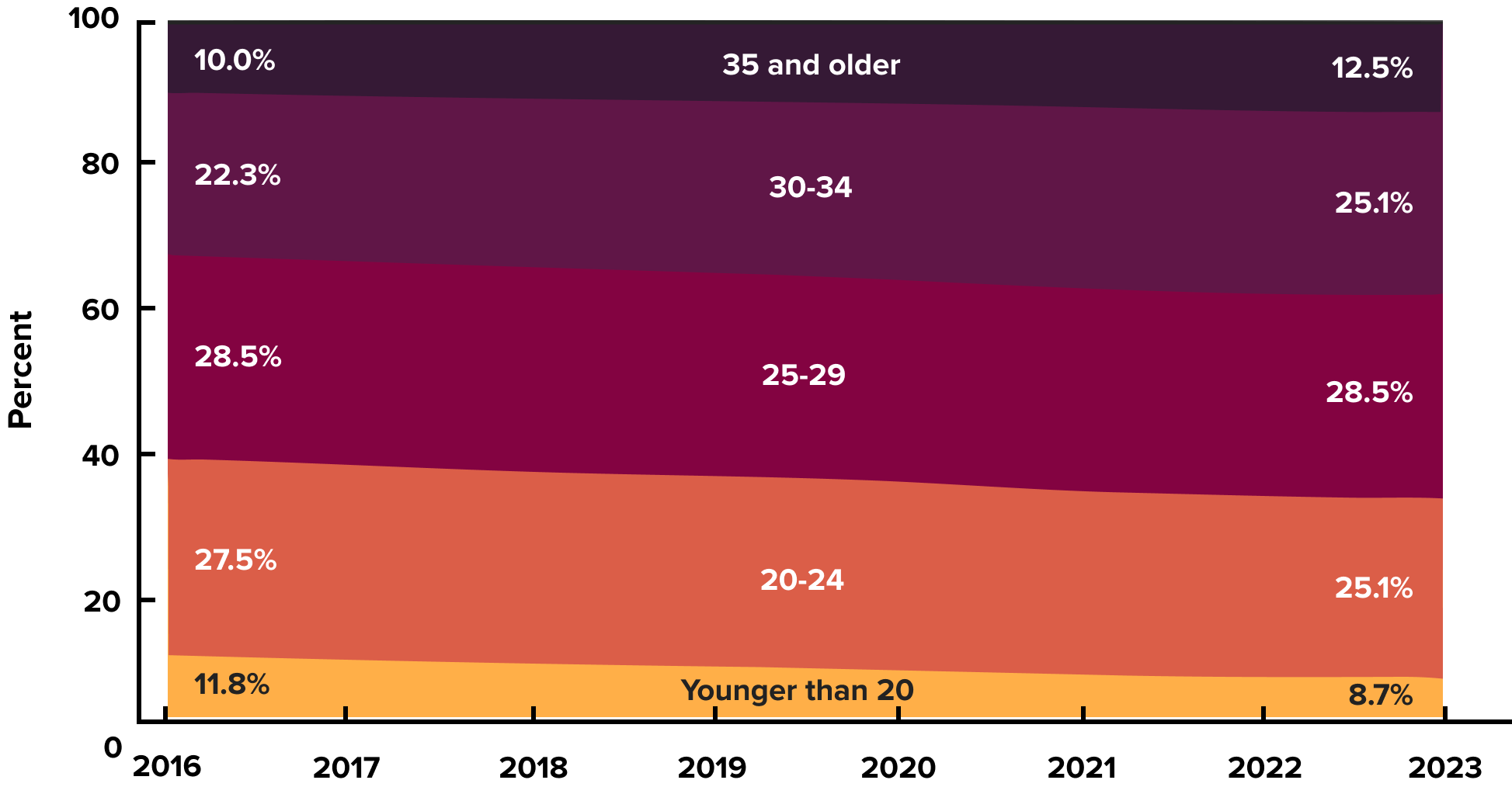

Changes in First Births by Maternal Age

From 2016 to 2023, first births increased among mothers aged 30 and older and decreased among mothers under 25, while births to mothers aged 25–29 stayed the same. Image courtesy of CDC.

As a result, more women are pregnant or recently postpartum at ages when breast cancer risk is already rising, and as mentioned earlier, later childbearing can also lead to delayed or incomplete post-lactational involution.10 These combined factors may help explain why PPBC is more common in women who have children later in life.

How does this information help us? Being aware of this risk allows mothers who have children later to take simple, proactive steps. Regular mammogram screenings, watching for any new changes in the breasts, and consulting a doctor promptly can make it easier to detect potential problems early. Since this type of cancer is relatively rare, doctors may be less aware of these risks.

Is there a genetic risk for PABC?

There have not been clear associations found between PABC and any known and widely tested genetic predispositions to breast cancer risk, such as BRCA mutations. However, the changes in the breast after childbirth share some similarities with menopause. In both cases, estrogen levels drop, sometimes precipitously, and the breasts undergo a major transformation—post-lactation involution at childbirth and age-related involution at menopause.8,10

Previous studies have found that women who carry the inherited KRAS-variant are particularly vulnerable to developing breast cancer during perimenopause or after removal of the ovaries, both of which involve sharp declines in estrogen.35 This raises an important question: might KRAS-variant patients also face an elevated risk of PPBC due to rapid estrogen loss after childbirth?

This question will be explored further alongside the ongoing MiraKind study of estrogen loss and breast cancer risk. We anticipate presenting preliminary results from this study early in 2026.

Turning awareness into action

Scientists are still learning about PABC, and there’s a lot we don’t know. Women and families can learn to protect their health through self-advocacy by understanding the basics of what it is, how it behaves, and what to watch for.

If you’re pregnant or postpartum, pay attention to any unusual changes in your breasts, and don’t hesitate to talk with your healthcare provider. Share what you learn with friends, family, and your community, and help make breast cancer a part of the conversation for mothers, new moms, and young families.

References

- https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/16805-breast-cancer-in-young-women

- https://www.cdc.gov/united-states-cancer-statistics/publications/breast-cancer-among-young-women.html

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9955856/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0344033823001139

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40211262/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21417804/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36192506/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2693781/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24678808/

- https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/oncology/articles/10.3389/fonc.2025.1420350/full

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41523-021-00378-7

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41523-020-00184-7

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1606507/

- https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0183579

- https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/genetics/articles/10.3389/fgene.2022.850195/full

- https://link.springer.com/article/10.1245/ASO.2006.03.055

- https://www.annalsofoncology.org/article/S0923-7534(19)39576-6/fulltext

- https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/EDBK_360970

- https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/tbj.13510

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18591310/

- https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1524-4741.2011.01201.x

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22785217/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3063387/

- https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cncr.26654

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8868503/

- https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanonc/article/PIIS1470-2045(12)70261-9/abstract

- https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.2012.45.6335

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3608871/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2693784/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8566602/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5090124/

- https://www.cdc.gov/breast-cancer/risk-factors/index.html

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40570233/

- https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr74/nvsr74-3.pdf

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4614527/

Leave a Reply