Genetics Variants and Cancer

To understand how your genetics affect your risk of cancer and how your body may respond to certain treatments, you need to know a little bit more about your body's DNA.

Your body is made up of trillions of cells. Every cell contains your DNA, which carries all the genetic information your body needs to function.

Differences in your DNA can impact your disease risk and help predict how your body will respond to treatments.

Genetic differences that you are born with are called "variants."

You can think of your DNA as a set of instructions. If those instructions have a difference when you are born, that difference is called a "genetic variant." That difference was inherited from one of your parents and is present in every one of your cells. Some types of variants are harmless, while other types can have a negative effect on your health.

Genetic variants that cause disease are referred to as "pathogenic genetic variants."

Some known pathogenic genetic variants include BRCA, CHEK2, and the KRAS-variant.10

Genetic differences that happen during life are called "mutations."

Understanding our terminology

Many sources, as we once did, use the term "mutation" to refer to any difference in a gene or genetic material. However, since the term "mutation" can have a negative connotation, the genetics community and the American College of Genetics and Genomics have started replacing the term "mutation" with "variant."

So while you will still see the term "mutation" used in other sources and in our older publications for any genetic difference, we now use "variant" to refer to genetic differences a person is born with, and "mutation" only for genetic changes to cells after birth.

Your DNA can also change, or "mutate," during your lifetime from environmental and lifestyle exposures. These changes occur from DNA damage not being repaired in one or more cells.8

Learn more about your genetics on our genetics 101 page

Both genetic variants and genetic mutations can lead to genetic diseases, including cancer9

Most cancer cases are considered "sporadic," meaning they occur due to genetic mutations (damage) in one or more cells from environmental exposures. Exposures like smoking, excessive sun, pollution, alcohol, and obesity.

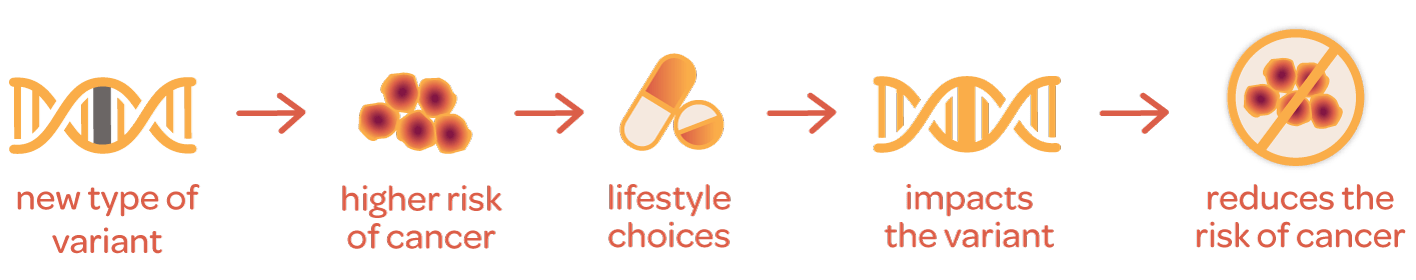

However, a recently discovered class of inherited genetic variants suggests that much more of your cancer risk is likely inherited from your parents. These variants can predict an increased risk of cancer.

More than that, this new class of variants appears to have identifiable triggers that lead to cancer and can influence cancer treatment choices for those who have them.

Understanding what makes this class of inherited genetic variants so unique

The class of genetic variants we study are distinct from others because of where they are, what they do, and how they can impact your response to treatments, hormones, and more.

Previously identified pathogenic variants affect the proteins a gene makes. These proteins are often created wrong and thus cause the body to grow or function incorrectly. Often pathogenic variants don't cause problems until a person is grown, and there is usually no way to know someone has a pathogenic variant until they cause a problem.

The pathogenic variants we study at MiraKind do not affect how proteins are made. Instead, they affect how proteins are controlled, as they are gene regulators, called microRNAs.

After helping you develop, a microRNAs' job is to protect you when there is stress, and DNA damage is a stressor. Suppose someone has a pathogenic genetic variant affecting how a microRNA works or communicates. In that case, when a stressor creates damage in a cell, requiring repair, the response may not be done correctly. They may cause a cell to make the wrong amounts of proteins, send proteins to the wrong place, or otherwise mismanage cell repair and communication. This misregulation of the DNA damage and stress response can lead to cancer.

Cancer choices

Since the pathogenic variants we study at MiraKind affect the microRNAs processes, our research has found they can help inform some cancer treatment and prevention choices.

Cancer prevention

This type of variant and cancer prevention

The KRAS-variant is the first example discovered of this unique class of pathogenic genetic variants to be associated with cancer and may be triggered by the loss of estrogen.

Discovered in 2006, the KRAS-variant is an inherited pathogenic variant associated with breast cancer,3 ovarian cancer,2 lung cancer,1 several other cancers,5,6 and multiple cancers in the same individual.4,7

Research has found a decrease in estrogen is associated with the onset of cancer in individuals with the KRAS-variant. For women, this decrease occurs during menopause. If women with the KRAS-variant take hormone replacement therapy (HRT) to replace that estrogen loss, data suggests they can reduce their risk of developing cancer.7

Cancer treatment

Uses for this type of variant in cancer treatment

Our research has also found that our unique class of variants can help inform some types of cancer treatment choices. For example, some variants from this class have been combined into panels that can identify patients with a higher or lower risk of side effects from radiation and immunotherapy treatments.

One example is a test called PROSTOXTM that has been developed for patients with prostate cancer and identifies if they are at a high risk of late genitourinary (GU) toxicity from radiation treatment.43

Looking forward

The future potential of this class of inherited genetic variants

In discovering this class of variants we have found one additional reason people develop cancer, but perhaps more importantly, a path to both identify "triggers" that cause cancer for some people, as well as genetic information that can be used to direct cancer treatment for the best outcome.

As we move forward with our research, we will deepen our understanding of this type of genetics and use this information to create more sensitive genetic tests, as well as create information to empower patients to make the safest informed decisions.

Subscribe to our newsletter to keep up with genetic cancer research.